Steel is real! That’s been my mantra for a long time. It still is, really. Interestingly, I didn’t grow up during the time when steel bikes were common place. Being of a younger generation, my childhood bikes were shaped by the waves of cheap imported aluminium, after the industry finally dialed in the production. Early aluminium experimentation was aimed at manufacturing racy, lightweight frames and this meant a lot of spontaneous failures and issues with longevity. Overengineering and advancement in heat treatment made aluminium a much more viable alternative to steel, by increasing the stress cycles the frame is able to withstand and making it less prone to dents and dings, this development alongside the promise of cheap manufacturing, was a crucial part of the early 2000’s aluminium boom. Alu is a pretty complete package when you think about it – cheap to work with, corrosion resistant, lightweight and durable. So, here I am making the case for aluminium, in a blog post about Titanium, which I started out by saying ‘steel is real’. Confused? I don’t blame you, welcome to my brain.

Even though my childhood and teen years were predominantly spent on aluminium bikes, I only own one aluminium bike nowadays. I shifted to steel upon returning to the world of cycling after a long hiatus. The reason was quite simple, I wanted to try something else and I’d always been curious about the supposed superior ride quality of steel. I also do think steel frames look better, with their skinny tubes and sometimes ornate lugged swagger. My foray into steel began with a ‘bog standard’ 4130 tubed Specialized from the late 90’s, but I have since expanded my fleet and now own a wide array of steel frames. My favourites being my Surly Karate Monkey, Cross Check and 1×1. Whether or not the ride quality is noticeably different from aluminium I couldn’t tell you, I’d say that my steel frames feel more compliant. They’re not as stiff feeling as my Zaskar, which is the only aluminium framed bike I own these days. But it probably is more down to wheel and tyre choice than anything else. So, what is it specifically that makes steel so real to me? I think it has to do with longevity. As alluded to by the title of this post, I value ‘all purpose’ bikes a lot, I like the utilitarian side of cycling. I want a bike to be able to withstand a bit of everything and I want my bike to be a lasting piece of equipment – I hope for all my bikes to outlast me. This is where steel comes to shine. While aluminum will eventually fail after a finite number of stress cycles, a steel frame can endure an almost infinite number of cycles, as long as the stresses remain below its fatigue limit. And should you be so unlucky and have a steel frame fail on you, there’s the option of repairing it. Because steel, unlike aluminium, does not require specialist welding setups or post-welding heat treatment. This is something that matters to me, because I see my bikes as a lifetime investment and though it may seem neurotic, I rest assured knowing that should one of my beloved bikes fail, I could take it to someone and have it mended. I could do that with an aluminum frame, but with the heat treatment it’d end up a very costly affair and in reality the repair wouldn’t be as strong as it would with steel. Aluminum is far more delicate to work with and is more sensitive to heat than steel. The heat from welding can significantly weaken aluminum in the heat-affected zone (HAZ), softening the metal and disrupting its microstructure. In contrast, steel is more resilient to heat, and its HAZ typically retains much of its original strength once repaired. So, there’s really no negatives to steel, right? No, don’t do it! Don’t say it! Not the R word….

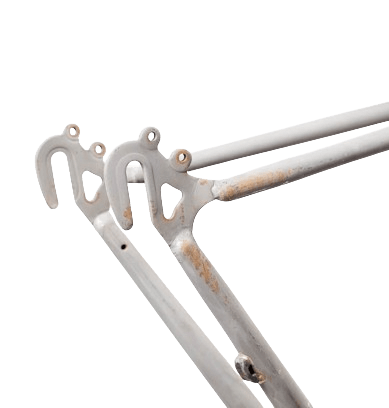

Sadly the one reality a steel frame owner has to come to terms with is rust. This is particularly an issue for those of us that live in northern maritime climates. I am from Denmark, a country which is surrounded by the roaring North Sea and the Baltic, so there’s little respite from the salty air. Even if I could escape the more coastal regions, I’d be exposing my bikes to salty sludge all through winter as the frost and ice sets in. And that remains my main gripe with using steel for an all purpose, all weather bike; corrosion resistance. A solid paintjob and well sealed components go a long way in protecting a steel frame, of course, but if you really use the bike year round, rust is pretty much inevitable. I treat my frames internally with CorrosionX once a year and do touch ups of surface rust as it appears, which gives me peace of mind, but it is a lot of extra faff. So, if not aluminium or steel – is there anything out there that’s better suited for the task of proper utilitarian cycling?

That’s when I realised that for quite a few years, unbeknownst to me, I’ve been internalising propaganda from a very vocal crowd. In almost every forum post about ‘which material is the best‘ and ‘oh no my steel frame is rusting what to do‘, there’ll be a few advocates for Big Ti. ‘This would never have happened if it was Titanium‘. I shrugged it off for a long time, admittedly because of the prices. A new off the shelf titanium frame is not exactly within my budget, a custom one even less so. It wasn’t until I stumbled over a bit of a bargain second hand, an early 2000’s Russian made Kocmo, that I decided to start my foray into titanium. Ti excels steel in a few ways, it’s more resistant to dings and dents and it has better fatigue resistance, with a higher fatigue limit that allows it to withstand more stress cycles than steel before failing. And last but certainly not least, titanium has superior corrosion resistance compared to steel and aluminium, as it forms a robust, protective oxide layer that shields it from even the harshest corrosive conditions. All of this sounds like the perfect concoction to build the ultimate all-terrain, all-weather goat, doesn’t it?

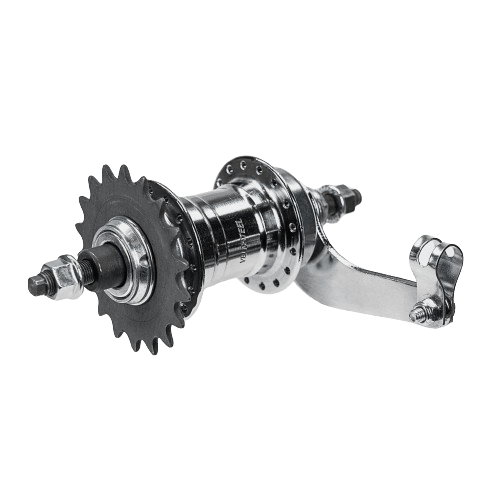

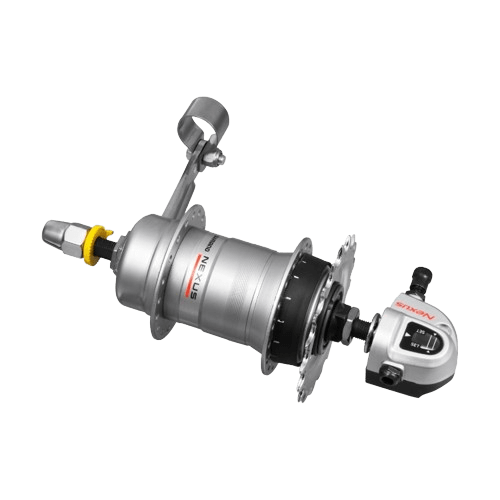

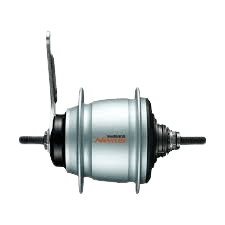

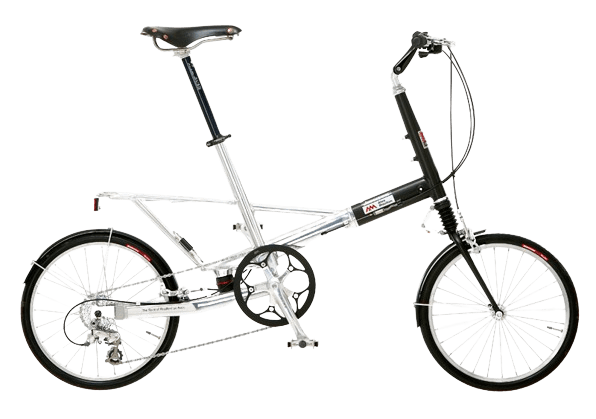

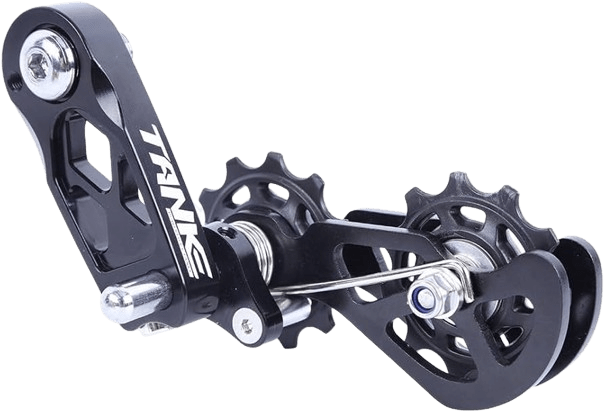

My Kocmo has gone through a few different outfits since I first built it up. At first I ran it 10-speed friction shifted, which didn’t last long. I quickly replaced it with an Alfine 8 IGH, which was a perfect albeit a bit heavy setup. Titanium usually lends itself well to lightweight builds, but my Kocmo is of the more overengineered, bulky persuasion – at least for Ti standards – which works well for my intended use. So, I’ve not been concerned with lightweight this and that.

The IGH setup served me well for commuting and gravel in the colder seasons, but as a mindless tinkerer, I can’t leave well alone and right now it looks like this, which is likely the way it’ll remain for a while yet. 1×11 and a set of comfy North Road bars, the result is a Randonneur-esque 26’er build which I’m quite proud of.

I have to touch on the ride quality too, and be as wishy washy as I was earlier in regards to steel vs alu. I insist on being able to tell a difference, I feel that my Kocmo is decidedly stiffer and somewhat harsher than my steel frames. The BB area of my Kocmo is less flexy than on my Surly’s, giving you greater power output at the cost of some extra harshness over bumpy terrain. I am actually pretty okay with that trade-off, as I find myself putting in a lot of tarmac hours on the Kocmo. But again, this perceived rigidity could be down to component choice. Regardless, my Kocmo has definitely been the better option for year round riding, I worry a lot less about maintenance and cleaning than I do with my steel frames. I like that Ti frames typically are finished raw, so there’s no paint to damage and all you have to do to brush up the frame is give it a scrub with a Scotchbrite and some lemon juice. Ti just oozes understated class even when abused, where neglected steel can look sad and ratty. Oxidised aluminium too. Taking all of that into consideration, I admit that I’m slowly coming around to it possibly being ‘the material for me’. But as the old saying goes, nothing is perfect. Being a neurotically obsessive person, I have to refer back to a previous point I made on repairability. For me a proper utilitarian bicycle is one that is strong, reliable and low maintenance. Now it should be mentioned that titanium isn’t particularly prone to failures, but there’s still this voice in the back of my head going… What if it failed, could I have it fixed? After some research the doubt started creeping in, because like with aluminium, titanium also calls for a fairly specialist repair process. Titanium, like aluminium, is very sensitive to heat and contamination so accurate temperature control is of utmost importance. And to further complicate things it requires an oxygen-free welding environment, achieved by using argon gas or a vacuum chamber. When you take that into consideration it becomes pretty clear that this is not something your average garage can sort out for you.

This means that if my Ti frame fails, I’d likely have to accept it being a wallhanger and that is something that doesn’t sit well with me. I know some of you reading this will find my insistence on repairability a bit much, but it matters to me and I believe it is an important consideration for anyone who is concerned with the disposable waste culture that we live in. I do feel somewhat assured by the fact that Ti frames don’t tend to fail that easily, and if they do it’s usually due to poor welding from the production line.

But hey! What about all those horror threads on various forums? I wanted to address this quickly because when doing research before buying my Kocmo, I was somewhat discouraged by the many people talking about cracking Ti frames.

But honestly I think this perception is somewhat skewed. There are far fewer titanium frames in circulation compared to other materials, so any issues are more noticeable due to the smaller sample size. Additionally, because titanium frames are a significant investment, owners who encounter problems may be more vocal about their experiences, amplifying the perception of frequent failures. I dare wager that the actual incidence of failure is significantly lower than it appears online. That isn’t to say you shouldn’t take it into consideration, especially if buying a second hand frame. I did notice that a good chunk of the failing frames that I saw online were older race frames. I always advocate for exerting extra caution when buying used race frames in any material, as these were designed to be as light as possible while being able to withstand the abuse of riding a season or two – they weren’t intended for long term use.

So, where do I stand on Titanium? Well, it’s complicated. I think I prefer my Kocmo to my steel frames. It feels bombproof, it’s less maintenance (stays pretty even when mucky!) and it rides nicely. But in terms of it being the ultimate ‘one bike you need’, it still falls short of steel simply due to the initial financial outlay and convoluted repair process. A steel frame gets you the best bang for your buck, a strong frame which can easily be modified and repaired. The only caveat is poor corrosion resistance, but let’s face it, unless you’re severely neglecting your bikes it is very unlikely that the rust will eat through your frame in your lifetime. I actually found it shockingly hard to find real horror pictures of rusted through frames on Google, so either Big Steel is keeping us in the dark with strict censorship – or maybe the rust issues in steel frames are vastly overstated. I am still very happy I dipped my toes in the world of titanium, though, and I’ve recently bought my second Ti frame (yet to be unveiled). I think it is worthwhile giving titanium a go, especially if you can find a bargain second hand. For someone like me, who owns multiple steel bikes, the price of a new Ti frame is not justifiable, especially considering the very marginal benefits. Ti still seems to cater more to the race-oriented, where weight to strength ratio is an important factor, and I would imagine the allure of exotic exclusivity is a selling point as well. But for a workhorse, I must echo the old proverb – steel is real!

Some may take offense to me not including carbon or stainless steel. My decisions for that are quite simple. Carbon actually ticks a lot of boxes, it is plenty strong, incredibly compliant on and off road, corrosion resistant and highly repairable (often quite cheaply), but also more sensitive. It is prone to damage by user error, installation of parts has to be done carefully to protect the integrity of the carbon layup. It also doesn’t handle impacts well, resulting in cracks or delamination, so it isn’t a material I’d trust for a more rough and tumble existence in cities or on the trails. In regards to stainless steel, I am very curious to see what the future brings. As of now it is somewhat limited by lack of tubesets, lugged construction and the higher cost of manufacture. I’d love to sample a stainless steel frame, though.