It is a well established fact that I am a shill for one particular branch of Shimano products. Namely the Nexus range. I have a deep love of these utilitarian, low budget hubs which has been stock offerings on pretty much every Scandinavian commuter I’ve ever owned. As such I get very excited whenever I see a mention of someone wanting to try them out on a bicycle that doesn’t quite conform to the typical “city bike” niche that the Nexus range has claimed. And there’s of course no reason why you shouldn’t pop a lovely 3 speed hub on your road bike or mountain bike. Or is there? Obviously there are some people who see Nexus hubs as disposable low end tat, and therefor wouldn’t put it on their bike. Those I can’t cure. But I think there’s another group of people, who likely would take the leap – if it wasn’t for this culprit;

Because if there is one type of shifter that has divided the waters more than anything, it is of course the gripshifter. They can be bulky, not always super ergonomic and lack versatility in terms of fitting.

A good example of this dilemma is if you want to use road type handlebars, which have a wider grip clamp diameter (23.8mm, they’re usually wrapped with bar cloth or tape) and as such you cannot fit the Nexus 3 gripshifter because it requires a standard 22mm grip diameter. You could go ahead and use something like a Hubbub adapter, which is essentially just a bar end plug that provides you with a clampable 22mm diameter tube for the gripshifter. It is not for everyone, though, as it isn’t the most aesthetically pleasing and the ergonomics of shifting are completely ruined.

But let’s say you’re not on a road bike and don’t use road type handlebars, you’d be fine right? Not necessarily. You may run into issues with grip area not being long enough to accommodate the bulky gripshifter, or maybe the handlebar has curves and is backswept, and that results in fiddly or impossible fitting of the shifter.

And last but not least, you have the people that just absolutely cannot stand gripshifters. Personally I think the “RevoShift” model by Shimano is the finest range of gripshifters ever made. But I can totally see how they’re not right for every application. Also, we’re all different – what works for you might not work for me. But I do believe I have the solution to this most dire problem. Not even the finest astrophysicists or most out of the box thinking philosophers could conjure up what I’m about to tell you. Just kidding.

After a very lacklustre drumroll, I can tell you that the solution is a thumbshifter. You can technically use almost any thumbshifter, because of the very simple workings of a 3 speed hub. Basically, we can break it down like this. We have our first gear, which is when there’s no tension on the cable. Then we have our third gear, which is cable taught. That leaves us with our one remaining gear, the direct drive, which is the second gear. That one is a crucial indexed position, and it is what we use to ensure that our bellcrank is correctly adjusted. What this means is that we can really overshoot our 3rd slightly, and as long as we consistently dial in that second, we’re good!

So, what we have to look for is a shifter with an indexing plate that has 3 positions, like for example, the ones that you use for a classic 3x front mech setup. Alternatively we can use one designed for another 3 speed IGH, like an old Torpedo Dreigang thumbshifter, or a Sturmey Archer one. The only thing that is crucial is that we can get that direct drive gear dialed in. Look around and see what you’ve got, the installation is really identical to stock with a gripshifter. Just install the cable into the thumb shifter, shift into the second gear on the shifter, then line up the yellow line in the bellcrank window and clamp the cable. Shift a few times and adjust with the barrel adjuster, repeating until it remains indexed in the direct drive (2) gear. Job done!

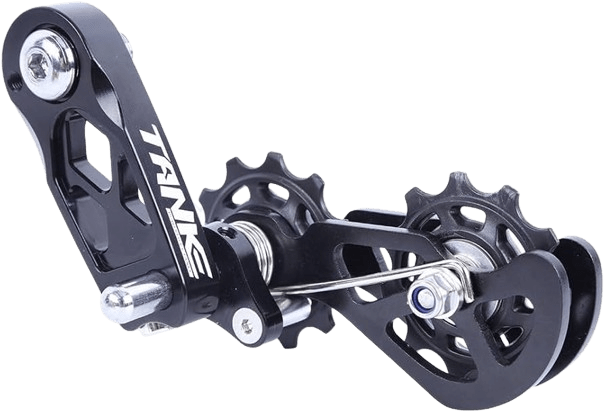

Now, not all shifters will be an ideal candidate for this. I have had varied experiences mix and matching, but I think most can be bodged into working – let’s not forget that people used to friction shift their old 3 speeds. I believe the late, great Sheldon Brown did that. But I would not recommend friction shifting, as it leaves too much room for error, and is likely to cause premature wear and tear to the internals. The safest bet would be to find something that is relatively close in cable pull ratio to the Nexus 3 and use that. So, that became my quest. I googled around for a while and eventually stumbled over a forum post, which mentions a certain Sturmey Archer thumbie model. Not only is it supposedly similar in cable pull to a Nexus 3 shifter, but it looks fantastic. The user reported having run it long term with no issues – even taking apart the hub to inspect. It is very versatile, being a screw-on type for downtube braze ons. Comes in two versions, bar end plug and flatbar clamp. As mentioned, can be unscrewed and popped on the downtube as well. Here it is, the Sturmey Archer SLS30:

I went for the bar end type, as I wanted to fit this to my moustache bars (23.8mm) on the Dawes. I have been using it for a little over half a year and have drawn the same conclusion as the user on that forum, it seems to be perfectly useable with a Nexus 3, though not officially compatible. Stays in adjustment, shifts as cleanly as the stock gripshifter and is far more classy looking. Here’s my Dawes Galaxy with the SLS30 fitted.

One thing I noticed about the SLS30 shifter, is that once you get to the 3rd position, there’s actually a bit of extra movement available, where it functions more as a friction shifter. I do not know if this is intentional, but either way it is actually a rather neat little feature as it allows you to pull a bit more cable for that 3rd gear, if the shifter is undershooting it. This makes it even more adaptable. Now I should add that I cannot find any actual specs from Sturmey Archer, and that’s why I haven’t included a cable pull comparison. A reviewer on SJS Cycles says that this works with Sachs too. Which sort of just confirms what I mentioned earlier, that cable pull isn’t the most crucial thing on a 3 speed gear hub, due to their simple nature. Nexus hubs are a fair bit more overengineered than their Sturmey Archer and SRAM counterparts, though, so time will tell whether or not this is a long term solution – but thus far I am happy with it. I will likely disassemble the hub come spring, next year, and inspect for excessive wear. But there you go, the solution to the IGH gripshifting woes, a sexy little thumbie which won’t mess with your Rivendell-esque aesthetic, hehe!