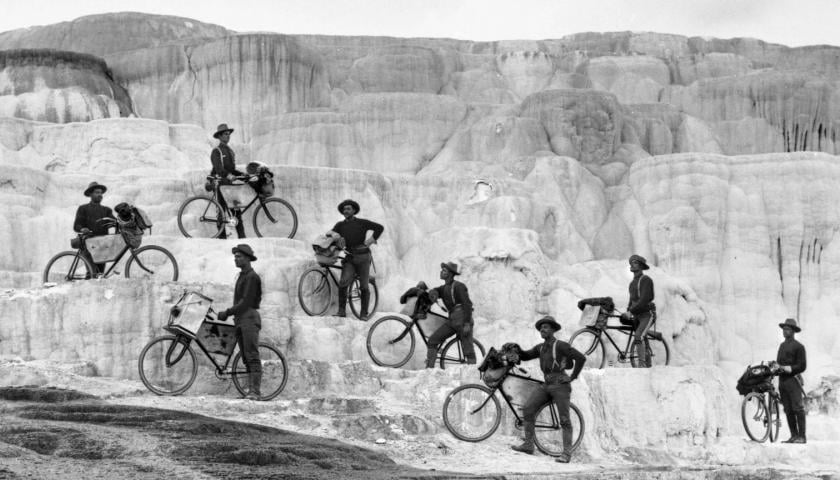

Recently I’ve been seeing a few posts here and there about these rather fringe drivetrains. I think they’ve become more common in the last 5 years, the so called 3×1 or 2×1. I remember going down the rabbit hole about them years ago. They’re by no means a new thing, I remember people, going back over a decade, talking about setups like this on MTBR and various other bike forums. It was usually brought up in relation to someone riding singlespeed, who then decided that they’d actually like just one more gear… or two… or three. And that always made me chuckle, when people suggest that it is an alternative to riding singlespeed, or worse, a more advanced and capable variation on a singlespeed bicycle. So, that’s what we will be exploring in this post.

For a long time most of my bicycles were exclusively singlespeed. I admit bluntly that a big part of the reason was that I was rather lazy and hated anything to do with drivetrain maintenance and adjustment. I thought it was a waste of time and I seemed to be pretty happy mashing away at the pedals. I feel that there is an intrinsic beauty to a singlespeed bicycle. The clean look and knowing that it’ll just keep on working no matter what you throw at it. It became a bit of a ritual at that point, to obtain a new (old) bike and instantly rip off anything to do with the gearing. But there’s a crucial thing to recognise in what I just said there. I removed parts to realise a singlespeed bicycle.

See what I am getting at? If you’re putting parts on which were required for a geared bike to function, and you add one or two more gears, well… You’re running a multi-geared bicycle! One could argue that, if the frame had vertical dropouts, it would be running a tensioner anyway – and how far removed is a tensioner from a derailleur really? Not very. So, yes, I can see how that could lead to a natural decision to go, “Well, might as well”, and add a front derailleur into the mix. And suddenly you’ve got a stripped down multi-geared pseudo-singlespeed bicycle which has none of the range with all of the problems of a fully geared bicycle. You’ve got two components that can fail and you still need to mess with cabling to shift that front mech, how’s that for a robust, low maintenance “singlespeed drive train”? I am aware that in saying this I am kind of throwing singlespeeding brothers and sisters with their tensioners under the bus. But I think we have to realise that running a tensioner is a bit bodgy and the ideal will always be track ends/horizontal dropouts or an eccentric bottom bracket/hub. The tensioner is just another potential point of failure, and if you’re riding in tall shrubbery and mucky terrain you’ll soon realise it is almost as prone to clogging up or snagging as a classic derailleur. That said a singlespeed bike, with a tensioner, is of course still singlespeed. It doesn’t shift and therefor wear less, resulting in lower maintenance and cheaper consumables.

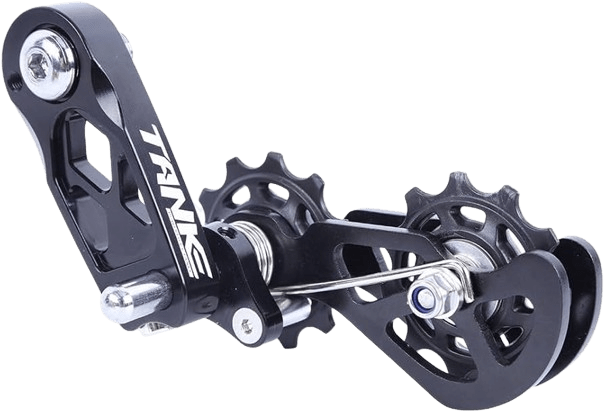

So, where does this leave us in regards to the fabled 3×1? I wanted some first hand experience, and took to building one again. I perused my wide selection of willing victims, and decided that the Scott Untitrack DH frameset, which I was given for free, would be a perfect candidate. Few random throwaway bits, a cheap Chinese “Tanke” tensioner and ta-da! A pretty fun little machine for almost zero outlay. I certainly don’t ride it as I would a singlespeed or an internally geared bicycle, as I still need to mind the tensioner and occasionally make adjustments to the front mech. As mentioned earlier – it is a pretty much just a very primitive iteration of my other geared bicycles, but that is not necessarily a bad thing.

The main benefit of a 3×1 is that I only have to contend with one shifter to get a useable range which is vaguely reminiscent of my 3 speed internal gear hubs. It is also lower maintenance as the rear doesn’t shift, there’s no cassette to grind down, and single cogs cost nowt and last practically forever. A front mech isn’t very prone to failure, sees less wear than a rear derailleur and is inexpensive to replace. And of course I’ve got no end of cheap triple cranks laying about so I’m sorted in that regard too. As such I do see it as a lesser chore than maintaining a classic 3×7, but it can’t hold a candle to the low maintenance and reliability of a singlespeed drivetrain or an internal gear hub. So, that remains my main gripe, people pretending these setups could be a singlespeeding alternative. So, from here on in I’ll just bluntly denounce this as any sort of alternative, and instead approach it as a more barebones externally geared bike. Anyway, adding to my earlier point on consumables, I opted for the cheapest 7/8 speed chains available, and in combination with a friction shifter, I don’t see myself replacing the cable or housing for the front mech anytime soon. I actually reused an old worn cable and housing, because the front mech is not a fine tuned instrument. It’s one step removed from using your big ol’ thumbs to slide that chain over. But all things considered, there’s probably no real cost savings to be made here. Older 7/8 speed drivetrains generally don’t wear that fast and the parts go for chip money. But at least it’s a bit less maintenance, right?…….right?

As you can tell, I reserve a level of skepticism. But I also think alternative drivetrains are important to talk about. Because it does seem like people are becoming more interested in having less gears, realising that perhaps the number war is futile. Maybe what we need isn’t always more gears, maybe we need gears that work specifically for us. I personally love having fewer gears with large jumps, most likely a side effect of riding my 3 speed internal gear hubs a lot, and so the 3×1 ticks a box. It is less cluttered and gives a sufficient range for my kind of riding. I know that some people go even further, and add a cog or two in the rear, and shift it using the barrel adjuster or by limit screws. I have a lot of time for that, because finding gear combinations that work perfectly for you goes a long way in increasing riding pleasure. I have mentioned in other posts that I find a larger quantity of gears somewhat distracting. And so I can totally see the thinking behind stripping away what isn’t needed. I think it is just important to stay grounded and nuanced, as not to create this “best thing since sliced bread” mentality. And I must admit I do find it all a bit funny, as it is becoming clear to me that we are slowly re-inventing the wheel over and over again. It will not be long until someone tries to sell us a double crankset with a 3 speed cluster in the rear. 1930’s called. But hey… I love a 1/8 chain as much as the next man so bring it all back! The Cambio Corsa is next! (hint: sarcasm)

Speaking of double cranksets, I really don’t get the appeal of 2×1. If you’re going to the trouble of using a crank with multiple rings, setting up a front derailleur and using a tensioner – wouldn’t it make better sense to use a triple for a bit extra range, and enjoying more gradual jumps for an almost negligible amount of extra weight? I think so. But anyway, as we reach the final notes here, I am going to reflect on my experience thus far. I definitely think I will continue riding my 3×1 Unitrack, because it is fun and different. It lets a component, which is generally perceived as obsolete and clunky, shine. I think that’s neat. A front derailleur is perhaps the most primitive shifting mechanism, and to let it do the heavy lifting is a good testament to how beautifully simple a mechanically actuated bicycle really is. I think that in many ways the front derailleur is the component that deserves more credit, for not only does it just work – it is pretty much unbothered by anything you throw at it and can last a lifetime. And with just one rear cog to deal with, you don’t have to worry about cross chaining or finding the right combinations which is often when the front mech becomes a faff. See? Plenty of good things to say about this 3×1 malarkey. Just don’t go shifting that thing under load going uphill, crunch! That is a job for a rear derailleur. But seriously, 3×1 perfectly useable setup. Ideal for someone that wants to simplify their shifting. Maybe you want to focus less on shifting and more on riding, maybe you live in a place that doesn’t really warrant god knows how many gears. Maybe you’re just bored and have a mish mash of crusty parts and you fancy building something that requires the bare minimum.

If you’re looking to do a conversion like this, I would recommend giving it a go first using that rear derailleur you likely already have lying about. Just dial in the limit screws to get it sitting near the middle of the freehub – may need to get longer screws, or clamp a piece of cable down and wind out the barrel adjuster. I would recommend keeping the cog relatively centered with the middle ring to give the crispest front shifting, but it’ll likely do OK with more inboard or outboard positions. Chainline is far more crucial with narrow modern chains, and their cassettes.

Now if you’d prefer to have a dedicated tensioner, all you need to look for is a double pulley one as they usually have more sprung range to accommodate the gear jumps. You could probably use a sprung one-pulley tensioner for a 2x, but the double pulley type tends to hold the chain more securely and some of them are even decided to handle front shifting. Inspiration:

I was going to use my Alfine, but adjusting the chainline on that is daft, using washers. The same thing really goes for the Rohloff and Melvin tensioners, they rely on washers too – for the Melvin they go on the pivot point. The one I decided to use, the Tanke, which I got cheap on AliExpress, simply clamps unto a metal rod ala the classic Surly Singleator. I like this better for easy adjustment.

Happy wrenching.